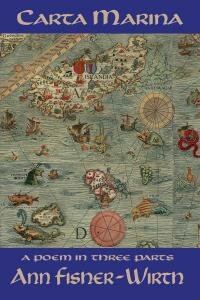

By Ann Fisher-Wirth

Reviewed by J. Gabriel Scala

Wings Press, 2009. 81 pages.

Lost to public knowledge for more than three hundred years, Olaus Magnus’ map of the Nordic countries, the Carta Marina, is the basis of Ann Fisher-Wirth’s third full-length collection, Carta Marina: A Poem in Three Parts. Using a variety of forms and a consistent chronology, Carta Marina… is one of those rare book-length poems that so masterfully sustains its narrative, so subtly maintains its urgency, that it cannot be put down once opened until the entire thing has been read – and then we must, absolutely must, turn immediately to the first page and begin all over again.

Lost to public knowledge for more than three hundred years, Olaus Magnus’ map of the Nordic countries, the Carta Marina, is the basis of Ann Fisher-Wirth’s third full-length collection, Carta Marina: A Poem in Three Parts. Using a variety of forms and a consistent chronology, Carta Marina… is one of those rare book-length poems that so masterfully sustains its narrative, so subtly maintains its urgency, that it cannot be put down once opened until the entire thing has been read – and then we must, absolutely must, turn immediately to the first page and begin all over again.

Beginning in late fall and moving purposefully and urgently to mid-spring, Carta Marina… brings multiple worlds – the physical, the emotional, the spiritual, and the intellectual – to light. As both a poet and an academic, Fisher-Wirth displays incredible skill in crafting each and every poem, and she leaves her laborious research out in the open – unapologetic – in a move that grounds the emotional highs and lows that bring us as readers to the brink of disaster.

The book opens with a bare facts description of the Carta Marina, situating readers in the historical context of the poem:

The Carta Marina, “the earliest map to present a fairly accurate picture of Sweden and its neighbouring countries,”* was completed after twelve years’ labor by the Swedish historian Olaus Magnus in 1539…Made of nine woodcuts, the map measures 170 X 125 centimeters.

And then, like the bear of the opening poem, Fisher-Wirth takes her scholarship and “presses it like a lover, / wraps one arm around its neck, sinks [her] teeth // into its shoulder” (3) – until we are lost in the swirl of finely crafted lines and gorgeous images, almost missing entirely the historical and cultural value of the work she’s done. Almost. Early poems in the collection guide us along the wooden contours of the map’s surface. It is a map of a people, to be sure, but the Carta Marina’s history – having been completely lost for a period of time, even to the point where its very existence was questioned – works as a metaphor for the poet’s lost history, for all of our lost histories freshly recalled, painfully remembered and seen again with new eyes.

Fisher-Wirth carves layers of narrative onto the surface of the Carta Marina. Using a diary format that keeps the reader grounded in time, the poem shifts deftly between breathtaking depictions of the Swedish landscape, correspondence between the speaker and her former lover, and anguished reflections on both a life lost and a life that is starkly, beautifully, simplistically steadfast. The tragedy lying in the foreground of the poem is that of the speaker’s child who “shifted and grew, an / elbow, a knee sculpting her side, its small life thrumming in her / bloodstream” (18) and the dawning knowledge of “the smear of blood on the toilet paper, / then at her walking / back to the bed, / still naked, / and everything different forever then” (16). Under the engraving of this loss lies another, more recent and shadowy loss – that of the speaker’s students, Chuck and Jonathan, who are so subtly woven into the text that the students and lost child blend and meld into the loss of all “the babies, the babies in their gray coffins” (26).

In the crevices of this loss lie the relationships – strewn haphazardly about. The speaker and her former lover exchange emails, ask long silenced questions, and the danger in the fact that he is “In love with me again—or, he says, still—“ (40) hangs precipitously in the air above the others: his family, her husband. And though Carta Marina… delves deeply into what it means to be human, to be inconveniently confronted and momentarily lost in what-might-have-been, it is the relationship sitting silently, patiently by that defines this masterful narrative. It is the moment of dawning realization that reminds us not only of our own humanity but of the humanity of those who surround us:

Peter and me naked in virulent color

sprawled on a beach, a sandy hillside, us scarlet,

cobalt, gold, electric—his beautiful burly torso, sharp knees,

cock lying soft against his thigh, beyond him my body naked,

us sloping gently flushed rosy and crimson, this was when I knew

we were married eternally, and I say “Yes, yes,”

to my friend, “that was a good vacation,” while all the while

I’m thinking, What have I done? What have I done? (43-44)

Carta Marina: A Poem in Three Parts wraps layer upon layer, blends old deaths with fresh ones, ties the steadfast silence to the raging roar, and covers it all under the “Red roofs” of Sweden, of Paris, “this clayey red / as if someone remembered Mississippi” (12). And this is where Fisher-Wirth’s brilliance really shines. Like true emotion and experience, one tragedy molds itself into the next, one great love slides atop another, until we are unable to see where the knife first struck, the individual cuts blur into a spectacular vision of pain and beauty. The Carta Marina lays Sweden bare as Fisher-Wirth’s poem of the same name lays bare the complexities of human loss, the compromises and sacrifices of human relationships, and the power of the human heart, “The split heart– / The heart still split—“. It is itself a map, whispering the cartographer’s secrets and guiding us always through “All this human love and anguish” (75).

–

–

J. Gabriel Scala received an MFA in poetry from Bowling Green State University and a Ph.D in English from the University of Mississippi. She has published poetry and reviews in numerous publications and her chapbook, Twenty Questions for Robbie Dunkle (2004), was published by Kent State University Press.

Pingback: Review of Ann Fisher-Wirth’s “Carta Marina: A Poem in Three Parts” « AngelSpeak