Jennifer Spiegel

I. Mid-Season Ponderings

Visualize a square circle. Can you do it?

I knew I wanted to write about “Lost” before I knew what I wanted to say.

How “Lost” Saved My Marriage: I Once Was Lost, But Now I’m Found?

That could work. The truth is I’m no lit-crit scholar; I’m a fiction-writer who likes to dabble in pseudo-criticism with a strong hint of creative nonfiction. So I could go into how my husband and I made this tacit commitment to watch “Lost” till the bitter end, after we checked it out (innocently) from the local library in August 2009, sometime around our fifth anniversary—and then we watched it three to four times a week until we were caught up with the rest of the world, before joining the sixth season frenzy. By spring 2010, “Lost” was deeply woven into our sinews, a part of us that would most certainly be missed at the end. Our marriage wasn’t really crumbling when we started—that’s a little Mark Twain-inspired exaggeration. But “Lost” gave us something together, something special. No joke. We cuddled on the couch throughout.

But, well, that’s about all I can say on the subject.

Moving on.

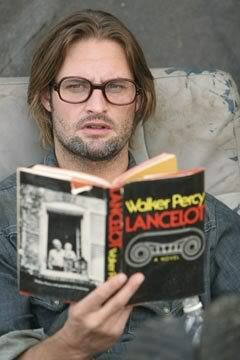

Sawyer--Seen here with Lancelot...

Lit TV. Gotta love Sawyer and his books. Who remembers that shot of Sawyer sitting on the beach in his makeshift glasses reading Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret? Who remembers?

Well, ultimately, it’s the end that matters most—to me, at least. How’s it all going to end? Here’s my opportunity to talk theory, talk shop, be included with the big guys. You know who you are. You Big Guys.

And I need a literary figure—someone legit to make this a case for “Lit TV.” Okay, Flannery O’Connor.

A Good Man is Hard to Find: Ben. I Think I Love Him.

No.

Everything That Rises Must Converge: “Lost” and the Redemptive End.

Got it. That’s the one. And did you know that Jacob was reading it when Locke fell out of the window in “The Incident, Part One” (season five, episode sixteen)? Don’t even go to “Lostpedia” (I know you already have)—it’ll just make you nuts with theories and literary references.

But what does that mean? Everything that rises must converge? The redemptive end, my friends, the redemptive end.

A question has haunted me as I’ve been sucked into “Lost.” I know we’re all intrigued. I know that. But I’ve relentlessly pursued my husband with one question: Do you think they’re gonna pull it off? Will the producers and writers successfully wrap it up? I mean, the end is everything. It’s not the process; yes, that’s part of it. But it’s the end that makes everything worthwhile. We marry whom we marry because of our faith in the end. If a relationship ends badly, the whole thing sucks. Come on, be honest: do you speak fondly of that ex-boyfriend who meant so much and then left you for another woman? You do not. Our religious beliefs are founded on the end. Only if Jesus is resurrected. Only if there are a new heavens and new earth. Only if there is both justice and mercy. The ends do justify the means. They really do.

So will the makers of “Lost” pull it off? Or are we all suckers for staying tuned—for six years? Let me say this now: If the narrative completely fails at the end, kudos to the producers for skillfully engaging us for so long. The joke is on us.

Here are some pertinent questions that have informed my own viewing: Is resolution necessary? Are unanswered questions or loose ends okay? In short, what do we demand of our narrative?

I demand resolution.

One friend (Penny Krouse, my critic and confidante) scoffed a bit at my obsessive ponderings over Sawyer’s wellbeing. (Yeah, I love Sawyer—let me tell my husband now: Tim, I thought Sawyer was adorable. Not as adorable as you, of course. But he was a doll.) Penny said that she needed for the show’s worldview to be revealed—through plot and character—for it to be a meaningful and thought-provoking work (March 24, 2010). Okay, so what is the show’s worldview?

Initially, I thought the show was about sanctification. This is from my earliest e-mail on the subject with Penny, with whom I like to engage in five-minute cultural theory e-mails:

The initial question we have: Why does this show appeal to us so much? And have you noticed that it is not unprecedented? There’s Robinson Crusoe, The Swiss Family Robinson, Gilligan’s Island, and even The Lord Of The Flies. We like the scenario very much; it’s got something universal. Not just survival, but the building of a workable world, using bamboo shoots if necessary. And this show too–the way it’s blatantly said in episode three: the tablet is erased; whomever you once were, you no longer are; you start over, do over. Racism, drugs, crime–BEGIN AGAIN. Sanctification.

This is from August 20, 2009—when my husband and I launched our togetherness project. Keep in mind that I was just getting started. The rest of the world knew about all this. Penny was patient, even mentioning Shakespeare’s The Tempest. I thought I was on to something; turns out, everyone was. But . . . .

Here we are. Six seasons later.

Of course we all have a slew of questions. What about those numbers? Why is Aaron important? What is the Island? And what about Jacob? And his nemesis, the Smoke Monster/Un-Locke? What about the parallel universe/dual time-line thingy? Is this some kind of statement on fate and/or choice? And what about the Dharma Initiative—is it now insignificant (a $%#@ red herring????) since the big issue seems to surround the opposing forces of Jacob and the Smoke Monster? Why is Charles Widmore so important? Why can’t they have babies on the Island? Should we be capitalizing Island? And I’d kinda like more info on the polar bears.

And we should also ask this: are there unacceptable endings?

It was all just a dream? It’s crazy Hugo’s film script?

Consider this e-mail message (May 6, 2010) from Arizona State University Ph.D. candidate in English, Jennifer Downer:

Is everyone going to get picked off one by one until only Jack survives? Because that would be majorly depressing. What I don’t want to happen: everyone but Jack dies on the island; meanwhile, the side-world is everyone’s chance to get things “right.” Dear writers: happy endings galore in the side-world do NOT make up for the fact that you killed off all the original versions in the other reality. So going back to what-I-demand-from-my-narrative, Jennifer, I demand that they don’t pretend that creating another, separate version where things turn out good solves ANYTHING about the original narrative (the one that got us interested in the show in the first place). That does not qualify as a redemptive ending.

I tend to agree.

Personally, I need some answers.

oo

II. Theory

Just a little, don’t worry. Theory in the softest way possible. I’m a fiction-writer. I can’t even write an abstract poem.

In the 1998 film Fallen, Detective Hobbes, played by Denzel Washington, investigates murders that involve Azazel, a powerhouse demon, who happens to enjoy singing “Time Is On My Side” by the Rolling Stones. In the end, the fatally-poisoned and demon-possessed detective is in his death throes. If the demon fails to find a new host, he too dies. This is the plan: Detective Hobbes purposely tries to commit suicide, thereby killing the demon and ending his murderous rampage.

And we watch with bated breath: will Denzel and this devil die?

Right before Hobbes gives up the ghost, a cat crosses his path; the demon exits the good detective and enters the feline. The perpetuation of unconquerable Evil. The camera pulls away and the credits roll while the Stones switch songs and sing “Sympathy for the Devil.”

Tim O’Brien’s novel In the Lake of the Woods (1994) presents a mystery. (Sorry, Kyle Minor, I’m about to criticize one of your faves.) The wife of a politician and Vietnam vet is missing. Perhaps she left her husband, wanting to escape his past and her role in it. Perhaps he killed her, leaving her for dead in the lake. We never find out. The end is a figurative question mark, an unsolved mystery.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) concludes with Jay Gatsby, romantic idealist and prisoner to illusions, lying dead in his pool, having been shot by the crazed garage owner George Wilson.

In Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), Humbert Humbert, sexual predator and perv, dies of coronary thrombosis while he’s in prison for a murder related to his ill-fated love affair/pedophiliac obsession with a fourteen-year-old girl named Dolores Haze.

Pulp Fiction, Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film, resolves with an old-fashioned epiphatic moment: Hitman Jules Winnfield, played by Samuel L. Jackson, decides to give up a life of crime and cold-blooded murder to walk the earth like Caine in TV’s “Kung Fu.” As he explains to Vincent Vega, played by John Travolta, he’ll “just walk from town to town, meet people, get in adventures . . .until God puts [him] where he wants [him] to be” (Tarantino 173-174).

In a postmodern world in which nothing is sacred, in which meaning is always up-for-grabs, in which Truth is mythology, narrative is inevitably doused in that which we lack: it can only echo our sorrows, either implicitly or explicitly. Is this the fate of “Lost”?

Once upon a time, characters had epiphanies; happy endings were possible; an “end” could be had. No more.

Okay, it is my contention that successful narratives have “redemptive endings.” Allow me to discuss what the “redemptive end” means and to illustrate that narrative isn’t a fruitless, hollow endeavor.

By “the Redemptive End,” I am not suggesting that narratives must end happily. This is a misnomer that needs to be immediately dismissed. “Redemptive endings” are conclusive endings that affirm meaning. (One might ask the following question: isn’t it presumptuous to assert that a writer knows what the meaning (of life) is? Why would you read if the writer had nothing to say? That a writer says nothing nicely—artistic merit—is not sufficient. The lack of content or meaning erodes the artistry.)

Check out contemporary fiction. Stories go out like a flame; the narratives are like windblown dandelions—they’re lovely, even proud, somehow barren; the sound they make is a “whiff.” When the book is closed, the whiff is swallowed by real-world noise. These whiffs are forgotten. Contemporary fiction can be highly forgettable.

Consider this analogy for a story sans redemptive ending: you’re taken to the edge of a cliff. That cliff is staggeringly beautiful and thrillingly dangerous and, though it’s a treacherous hike, you’re barely aware of strain since skilled hands led the way.

Then, you’re left there.

You’re not pushed; you’re not taken to safety. Rather, you’re left on the edge without direction. You’re left for dead!

This is the effect of the whiff, the lack of the redemptive ending. It’s like being stranded.

The concept is simple enough: a redemptive end is conclusive and it affirms meaning. “Redemptive” does not necessarily have religious connotations. The grand finale isn’t inevitably didactic or preachy, happy-go-lucky or warm and fuzzy. Rather, it’s meaningful. And, there’s a sense of closure.

A discussion on the redemptive end begs another question: what is art? At the risk of being overly simplistic, consider John Gardner’s words in On Moral Fiction, in which he equates art with a universal wound in the human condition, which cries out for healing (181).

I like this suggestion. First, it implies that art hurts. Second, it points out the universality of the hurt. Art is serious because it’s human; art is for humans—all of them.

One aspect of being human is holding to belief systems and possessing worldviews. Despite this, our fiction seems to keep away from topics deemed “too personal” due to their philosophical or spiritual nature. For me, the personal, the spiritual, and the philosophical are the most compelling. Aren’t these the themes of the great novels? Hasn’t “Lost” touched upon—even if only in TV fashion—a number of these? Who wouldn’t answer, “Yes!”?

All of you former grad students may remember Frank Kermode’s The Sense of An Ending which examines our need for resolution. Like Gardner, Kermode’s theorizing is secular. He argues that novels necessarily have resolutions:

As soon as it speaks, begins to be a novel, it imposes causality and concordance, development, character, a past which matters and a future within certain broad limits determined by the project of the author rather than that of the characters. They have their choices, but the novel has its end. (140)

Traits we discuss in fiction-writing like cause-and-effect, time scheme, and character development assume meaning. We string words together in causal relationships. Fiction-writing is meaningful because it pursues sensical relationships. Beginnings assume endings. This assumption affirms meaning.

James Joyce articulated the idea of epiphany, a secular moment of truth. For me, epiphany is the very feature that allows me to dwell on the personal, spiritual, philosophical. This moment of clarity or enlightenment ushers in meaningful conclusion. Epiphany paves the way for redemption.

Has contemporary fiction abandoned epiphany? Perhaps epiphany is impossible in postmodernity. When relativism reigns supreme, revelation and illumination are scarce; after all, who’s to say what’s revelation and what’s not?

This does seem to be a stumbling block for the redemptive end. How can a conclusion that affirms meaning be advocated within a relativistic milieu? Think about two of my favorites: Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Where would these novels be if good wasn’t good, and evil wasn’t evil, if all were relative? Is racism ever okay? Conviction works against relativity; conviction has to do with naming absolutes and determining good and evil. It isn’t shy about finger-pointing.

These, then, are the features of the redemptive ending: conclusiveness (as opposed to ambiguity), meaningfulness (as opposed to meaninglessness), epiphany (as opposed to the sound of a “whiff”), and conviction (as opposed to relativity).

Only The Good Die Young? Let’s consider a few works.

Tim O’Brien is heralded as a great writer for good reason. His collection The Things They Carried brilliantly renders abstractions concrete by taking the dictum “show, don’t tell” to heart. He practices what he preaches. His novel In the Lake of the Woods (1994) is, in essence, an articulation of a philosophy on narrative.

As far as he’s concerned, we don’t really know if the good die young.

On the fifth page, protagonist and Vietnam vet John Wade says the worst thing he can think of saying, “Kill Jesus” (5). Kill can mean eradicate, exterminate, or murder. With this brutal mantra, final causes, absolute meaning, and a concept of singular Truth are abolished. Vietnam and any so-called “sins” committed there (or at home) are eliminated by removing causation.

O’Brien deliberately leaves the book unresolved. We never find out what really happens. O’Brien writes, “To know is to be disappointed. To understand is to be betrayed” (242). In the last footnote, he writes, “ . . . there is no end, happy or otherwise” (301). If the logic of this narrative were followed, the conclusion is rather interesting. If death is meaningless, life is meaningless. If life is meaningless, the book is pointless. Reading it is even more so. Redemption belongs to the realm of certainty; O’Brien affirms uncertainty. I love his prose; he’s philosophically interesting. But, but, but . . . .

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby can be studied for many things, including its redemptive ending. In this, the “great” die fairly young.

How can a book that ends with the death of the “hero,” if you will, be considered “redemptive”? This illustrates how the redemptive ending is not necessarily happy.

I don’t know about you, but I like Jay Gatsby. I know there are a whole slew of people who find him pathetic (these tend to be the same people who don’t really like my good friend Holden Caulfield) because he’s frightfully self-indulgent and terribly blind. But I’m fond of him. Say what you will.

But Jay Gatsby doesn’t live in the world of which he dreams. In fact, that world doesn’t exist. Fitzgerald could have done several things. He could have written a happy ending. Perhaps contrived and false, Gatsby and Daisy could have lived happily ever after. Fitzgerald could have gone for ambiguity, maybe hinting that there was a flutter of pulse in the bullet-ridden body of the Great Gatsby.

Instead, he gave Nick the epiphany. Jay Gatsby doesn’t survive—he simply cannot survive in this world: he either has to die or change. But Nick is transformed; he’s redeemed. Fitzgerald uses his narrator’s first-person perspective to raise Gatsby’s life to the level of universal metaphor. The novel is not only a personal tale of one man; it’s a universal tale for all men and women. The narrative transcends its circumstances to address the human condition. Sad and unrelenting, it affirms meaning in its refusal to let Gatsby survive with his illusions. The novel becomes a treatise on our hopes—perhaps a vision of the new world or an American Dream—and the potential for realizing those hopes.

Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955) also provides an example of a secular redemptive ending. About the good dying young, it’s tough to say. No one’s very good.

Humbert Humbert’s epiphany is that he needs redemption; this is the corner he turns. He realizes that he requires salvation from his sins. As far as he’s concerned, religious redemption will not do the trick. The imperative thing to note here is that Humbert Humbert does undergo profound change: he recognizes what we might call “sin.” He experiences conviction, which is only meaningful because he recognizes a distinction between right and wrong. His attraction for a girl named Dolores is wrong; it’s not a relative issue. Age, maturity, circumstance—it doesn’t matter; Humbert Humbert was wrong.

But he doesn’t find spiritual solace. His redemption is artistic. Nabokov’s secular redemption is an artistic redemption. Humbert abandons spiritual solace, clinging to art:

Unless it can be proven to me—to me as I am—that in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless this can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery but the melancholy and very local palliative of articulate art. (283).

Artistic redemption—in contrast to spiritual redemption—is palliative; it abates the symptoms; it softens the intensity of despair. Artistic redemption, Humbert Humbert concludes, is the best he can do since spiritual redemption is a no-go. Also, he realizes that if no crime were committed, life is a joke. In other words, if there’s no such thing as sin—or, as in Tim O’Brien’s novel, if causation is abolished and Kill Jesus is an a-okay thing to say—life is a joke; all is meaningless. Humbert Humbert, in accepting responsibility for what he’s done, affirms that life is meaningful. The redemptive end doesn’t take life lightly.

Finally, we turn to Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, the most blatantly redemptive and potentially offensive of the bunch. In this, it’s decidedly not the good dying young.

This film can be seen on two different levels. First, there’s a quest for prosperity (plot-related). Second, there’s a struggle between good and evil (theme-related). Rendered in an unorthodox, non-linear, pretty postmodern narrative form, the film’s content is blatantly moralistic and non-relativistic. It distinguishes between good and evil, and glorifies one over the other. Its title makes pulp ironic.

Ultimately, it’s spiritual redemption that resolves this film. Along the way, Jules grapples with biblical interpretation and divine intervention. Tarantino reveals his characters’ wrestling with Christian doctrines on evil, cleanliness, and ransoming. Evil is treated in the scenes surrounding The Gimp. Like Humbert Humbert, Butch (played by Bruce Willis) identifies evil; he’s not at all wishy-washy about it. He doesn’t succumb to relativism. Though he’s not “required” to save his enemy’s life, he does so—because evil is a profound and terrible thing. Cleanliness is explored most obviously in Jules and Vincent’s efforts to clean the car after a guy is accidentally killed in the backseat. While the rinsing of blood off their persons may be reminiscent of Pontius Pilate declaring his hands clean from the blood of Christ, Jules and Vincent tellingly discuss forgiveness as they scrub the car interior. While sanitizing the car, they ponder the forgiveness of sins. Spiritual and physical cleanliness haunt their dialogue just as sin and blood mingle on celluloid. Christ “ransoming” the lives of sinners is illustrated in the way Jules spares the lives of Pumpkin and Honey Bunny during a thwarted-diner robbery. The film is a modern-day parable.

For all its offenses, Pulp Fiction is highly, even religiously, redemptive.

In Fallen, Denzel plots to kill a demon by killing himself. He makes a human trap of his own body—forcing the evil spirit to have no other choice but possession. He smokes a cigarette laced in poison and kills the current host in a secluded area. As predicted, the demon comes aboard Denzel. But our hero forgets one thing: wildlife. The demon leaves Denzel for dead and finds a new host in a cat. And so, despite the twists and turns of the filmic narrative, the end leaves us nowhere different than we were at the beginning. Satan is still on the loose. It isn’t meaning that’s affirmed—it’s evil. The viewer walks out, thinking, “Wow, life sucks.”

Is this what we want? Should our narratives go nowhere? Should we learn nothing? Are we to believe that life is empty? Do we want such disappointment?

So, “Lost.”

The end is near. Give me redemption.

00

III. Spoiler: Everything that Rises Must Converge

Go back to that square circle. I bet you can’t see it.

So, very little was said about Flannery. In truth, she was just a diversion to get you to read. A big guy, remember? I needed her. My guess is that she’d heartily agree with me. But, yeah, she was a diversion.

The truth is that, though there have been other memorable show finales (“M.A.S.H.,” “Cheers, “St. Elsewhere”—for me, “Seinfeld,” and “The Sopranos”), this essay is about “Lost.” And, well, the show utterly failed on all counts already mentioned. I seem to remember learning in some very early Creative Writing 101 class that it’s a bad idea to end your story by (a) making a phone ring which wakes up your protagonist from this amazing, thought-provoking, beautiful Kurosawa-like dream thereby rendering the narrative a complete though lovely figment of the imagination, or by (b) revealing that everyone died or is dead.

Is it me, or did that just happen?

Well, I don’t need to go on and on, repeating all the thoughts we’re hearing ad nauseam. Like many, I immediately checked out Facebook for some public opinion, and was relieved (yes, relieved) to find many incensed writers. As far as I’m concerned, that’s a good sign.

So, yes, we’ve heard it all before. The writers didn’t plan for the show to last beyond a couple seasons. The cool guy who played Mr. Eko didn’t like Hawaii. Ben was only signed for three shows. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

And we’re still left with unanswered questions: So what was the deal with Aaron, the polar bears, Walt? Why couldn’t women have babies post-Dharma? Was the Dharma Initiative pure red herring? The underwater thingy—just an interesting visual? Empty but artistic? Why did the Smoke Monster/Un-Locke/Esau want to get off the Island so badly, but it seems like Jacob had no trouble at all making little visits to see the main characters in their pre-Oceanic lives?

And, of course, I can’t/won’t get away from some even more basic questions: Origins or First Causes. Allison Janney’s last-minute appearance, the unexplained birth of Jacob/Esau or Romulus/Remus, the unexplained golden light/Emerald City—all of it. Something doesn’t come from nothing. There really aren’t any square circles. No matter how seductive the mystery has been, there’s no mystery at all if it’s nonsense. These “Lost” artists (I will give them that) pushed the TV narrative to its artistic limit, but a narrative without a god fails? Bravo to you, “Lost” folk. You did it. Joke on me. I watched furiously/vivaciously/anxiously. I’ll miss you. I mean it.

Back to Flannery: a good man is hard to find?

So, too, a good story is even harder to find.

–

–

Dzanc Books will publish Jennifer Spiegel’s collection of short stories, THE FREAK CHRONICLES, in 2012. Additionally, Jennifer has an MA in Politics from New York University, and an MFA in Creative Writing (Fiction) from Arizona State. Having taught composition, literature, and creative writing at the college level—including several fiction workshops for ASU’s Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing—she continues to teach a variety of on-line university courses. Her work has appeared in several anthologies and journals, ranging from THE GETTYSBURG REVIEW to NIMROD. Recent work can be read in the May issue of PANK online.

♦

WORKS CITED

Gardner, John. On Moral Fiction. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1978.

Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Lolita. New York: Vintage International, 1989.

O’Brien, Tim. In the Lake of the Woods. New York: Penguin, 1994.

Personal e-mail from Penelope Krouse. March 24, 2010.

Personal e-mail from Jennifer Downer. May 6, 2010.

Tarantino, Quentin. Pukp Fiction. New York: Miramax and Hyperion, 1994.

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of Volume 15, which will be available July 1, 2010

Pingback: Emprise Review // Flannery O, Lost, and The Redemptive End

Pingback: I Have So Many Things to Tell You « Amber Sparks

Pingback: Volume 15 – Available NowEmprise Review | Emprise Review

Pingback: PANK Blog / July Is Almost As Hot As PANK Writers