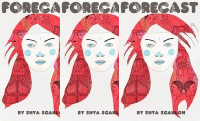

Reviewed by Adam Tavel

2011, Salmon Poetry

72 pages, paperback

To ask an American poet about international verse is often a waiting game, wherein one counts how many ticks of the second hand it takes for the responder to sing Neruda’s praises, quizzically gaze out the window, and deftly change the subject after a dramatic pause like a Wes Anderson protagonist. With the proliferation of, and plurality within, our many aesthetic cliques, it is lamentable that so few of us (this reviewer included) break out and explore the many emerging voices in the grand chorus of English language poetry. Such were my sentiments as I recently devoured Adam Wyeth’s mature and emotionally nuanced debut, Silent Music, as its central themes of divorce, transgression, and identity (in this case, Anglo-Irish) are vital to our Yankee discourse, but more importantly, his is an impressive and rangy collection that sidesteps the plangent gestures that so often mar first books.

Equally skilled in form and free verse, Wyeth displays the variety, zest, and invention one finds in the early work of Heaney and Lowell, since his best poems unfurl with organic pathos, rugged bravado, and rustic charm. Time and again, poems such as “Rough Music,” “Dad,” and “Blackout” occupy a third space that defies the quaint artificial division between lyric and narrative, whether Wyeth takes domestic violence, divorce, or the loss of innocence as his subject. Indeed, Silent Music is unflinching in both subject and theme, too—just in the first half-dozen poems, both poet and reader confront colonialism, landscape, grief, alcoholism, memory, and belonging.

“Butterfly Daughter,” a brief Dickinsonesque vignette from late in the collection, is a fitting representation of Wyeth’s strengths, since its ballad meter and gentle understatement capture the duality of a rapturous young girl imprisoned by the world (and perhaps the Holocaust, too, depending on how one interprets its final line). It is worth sharing here in its entirety:

Each morning before school

she prises herself from her cocoon,

a wood nymph – from the depth

of the earth – transforming in her room:the painted lady, marbled white,

meadow-brown, orange-tip,

hairstreak, every pattern and hue,

then takes off into the Adonis blue –her peacock wings opening –

weighed down by a festoon of bling.

A new person each day she leaves –

a clouded yellow heart on her sleeve.

Such ache is the foundation of many first books, but Wyeth’s bawdy humor keeps Silent Music afloat through its weaker poems, which are few. When the moment calls for wit, Wyeth prefers to play class clown rather than the wry wielder of irony, so it is impossible not to chuckle at the book’s coarser moments, such as “Life as Shit” (where two lads actually taste their own scat) and “Telepathy,” which is merely a blank page. (It is worth noting that both of the aforementioned poems made this reviewer guffaw aloud on first reading, despite the fact that I read them in the emergency room with a broken bone.)

Silent Music is also commendable for its formal ambition and arrangement, both of which display Wyeth’s commitment to Frost’s famous commandment that the book itself serve as the ultimate poem. The bottom-up lyric “Sunrise” precedes the witty haiku “Waiting for the Miracle at Ballinspittle Grotto,” while the sonorous sonnet “Apples” follows the Oedipal couplets of “Cinema Complex”; these are but two of many instances where Wyeth achieves greater resonance and echo from his meticulous sequencing.

At the heart of Silent Music is Wyeth’s double consciousness, as he straddles British and Irish identities and finds neither to be a true encapsulation of the self. Such searching, however, takes on the force of metaphor as the collection progresses—in poems such as “Deoch an Dorais” and “The Long Run”—since the poet repeatedly attempts to reconcile the daily struggles of our material lives with the brief communion we find in the poetic experience. For Wyeth, it is a communion worthy of awe despite our many sufferings, and the candor, craft, and lilt of these poems are a testament to his faith in language. It is a language we share, after all, stretched across these many miles of sea.