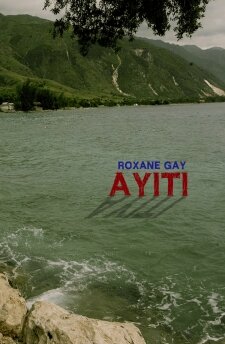

with Roxane Gay’s Ayiti

Artistically Declined Press, 2011

126 pages

Reviewed by j/j hastain

As someone who rabidly composes and reads mixed-genre works it is often the case that I can only open a book of “prose” or “stories” and read a small portion of it before I begin to get distracted or frustrated. I admit that I am a stimulus junkie and the usual pace of more traditional prose or story-based works is hard for me to stay in.

However, Roxane Gay’s Ayiti, coming out in traditional-ish sentences, is far from traditional prose or story. Rich/rife(?) with octane eroses and griefs, Roxane’s book is an acidic opera. I call Ayiti opera because of the way/s that it employs and embodies content not as linear drive through a lengthy span of pages (as is often the case with more traditional narrative) but poetically—rendering these valleys of sensation and collapse that force a reader into new ways of gauging its content—that force us into new ways to gauge its content as that content moves into our bodies. Ayiti is content that stays inside.

However, Roxane Gay’s Ayiti, coming out in traditional-ish sentences, is far from traditional prose or story. Rich/rife(?) with octane eroses and griefs, Roxane’s book is an acidic opera. I call Ayiti opera because of the way/s that it employs and embodies content not as linear drive through a lengthy span of pages (as is often the case with more traditional narrative) but poetically—rendering these valleys of sensation and collapse that force a reader into new ways of gauging its content—that force us into new ways to gauge its content as that content moves into our bodies. Ayiti is content that stays inside.

If a reader were to pick up this book as a “book of prose” or a “book of stories” and bring along with them all aspects of what those terms traditionally and historically mean, they might be met with deluges of sensation they were not exactly expecting. I am stricken to stay in Gay’s Ayiti because there is so much in it that I am not sure about (un-resolvable) while simultaneously there is so much within it that makes me somatically sure.

The following is some of what I feel unsure about in Ayiti: are the many gorgeous scenes in this book premeditated? Meaning (due to my fondness of how Ayiti works as a sensation-inducer), how was this book actually composed? How much of it relates to the writer’s own life? How much of it is imagined? How relevant is that question if this is not a memoir? How much of the stories are created from feeling / desire vs actual event? I am interested in asking these kinds of questions because the meta-works within the whole book have incredible stamina. They don’t stymie. They build and they enliven.

The somatic sureness I mention comes from the way that Gay’s gorgeous phrases almost combust in on themselves, exploding initial sensation into a thing that might make weeping—I am saying I kept grunting and moaning out loud (which means truth?) as I came into contact with these shapes of phrase that are almost sensory-ly an eternity / infinity sign: “He was always overcome with the vague feeling he had seen her somewhere before while she was overcome with the precise knowledge that he was the man of her dreams” [] “the stone path to his front door was lined with the tears and soiled panties of the women [he] had sexed then scorned” / “My mother recalls how her mother wailed, her voice pitched sharp and thin, cutting everything around her. In the front yard of their modest home, a large coconut tree fell, its wide trunk split neatly in half. The fallen fruit rotted instantly” / “She took river mud into her hands, eating it, enduring the thick, bitter taste”[] “she drank the memories in that water” [] “we chew on our pride. The dirt we do not eat.”

Now to include the eroses: “[He] will find comfort in the arms of a woman who is not his wife. He will go home with her and in the darkness, as he cups her breasts with his hands, and listens to her breathing against him, as he presses his lips against her neck, and shoulder, then licks the salt from her skin, he will imagine she tastes like home” / “I think about his teeth on my neck and the weight of his body pressing me into our bed. Sex is one of the few pleasures we have left” / “He sinks his teeth deeper into me and I can no longer see the fine line between pain and pleasure” / “He gently rolls me onto my stomach and kneels behind me, removing my panties as he kisses the small of my back. His hands crawl along my spine and again I can feel their wisdom as he takes an excruciating amount of time to explore my body. I arch towards him as I feel his lips against the backs of my thighs and one of his knees parting my legs. I try and look back at him but he nudges my head forward and enters me in one swift motion. I inhale sharply, shuddering a moan trapped in my throat. [He] begins moving against me, moving deeper and deeper inside me and before I give myself over, I realize that the sheets are torn between my fingers and I am crying”—these luscious and non-abbreviated sensation-hubs feel to me like prurient rooms where necessary but usually not-so-obviously-elucidated erotic grafts are taking place. These are the details of bodies accruing themselves along a stratum of need and it is the ways that these phrases (indications of the bodies) feel indelible to human existence and experience that makes them locate me so rooted-ly in Ayiti. I see my own need to be bound in them. Here I get the gift of seeing that the bondages that I need to experience both mirror and contrast the particular binderies of others.

Then to the griefs: “I make so many promises I cannot promise to keep” / “When he was inside her, she thought her heart might stop it seized so painfully” / “They followed us for weeks until a white man went missing and my story no longer mattered” / “I hung up because he was lying and he didn’t know it” / “There is no time for anything tender” / “My grandmother ended up in the river. She found a shallow place. She tried to hold her breath while she hid [] there was a moment when she laid on her back, and submerged herself until her entire body was covered by water, until her pores were suffused with it”—the shapes and phrases of the griefs (I omitted so many that I had written in my notebook for sheer consideration of length of review) strike. In Ayiti there are inter-cultural violences (via soldiers slaughtering cane workers), there are cross-cultural violences (via kidnapping and rape of an American woman in Haiti), there is information about the anguish of cross-cultural pressures to appropriate to American norms and standards (“HBO”), there is class and racial violence between American men and the Haitian women that they pay to belittle via sexual force / encounter behind boulders on empty beaches.

Perhaps it is a quality of genius to make the embodied realms of eros and grief less and less delineate-able (oh threnody!): “A popular lullaby from her country, about a mother with thirteen children. The mother kills one child to feed twelve, so and forth until she is left with one child, whom she also slaughters. Finally, she returns to the middle of a cornfield where she slaughtered the other children, and slits her own throat because she cannot bear the burden of having done what needed to be done” / “He ate her food. He shared her bed touched her body with his soldier hands; he filled her and frightened her and she felt something she didn’t understand” / “The warmth of her body, the way she welcomed him inside her, the taste of her skin were all things he would walk away from” / “She ran out onto the street, threw her hands in the air, stared into the incandescent sun. She cried as the light spread over her. A joyful sound vibrated from her throat, through her mouth and into the city around her”—Gay has made Ayiti an incandescent vividity–a place where forms are forced into varying states of subversion because they are in the life that subsumes them–because they are not transcending via leaving but instead via deeply living that life.

Zora Neale Hurtson dug into the cultural histories of the Zombi(e) in Haiti (see the return of Felicia Felix-Mentor after her death and burial at age 29) and in that digging found scientific grounding (and not just imagination or ceremonial relevance) for the case of zombi(e)s. Or Zombi(e)s as partial animates which are under the control of the “bokor.” How sharply you mirror many of the characters in Ayiti. Characters with no systemic privilege (context) from which to compose resolutions to the trials and griefs of their lives (“we will never have enough money to leave here”). Or Zombi(e)s as partial animates without their own will. How sharply you contrast many of the characters in Ayiti. Characters who have nothing but their own will to push themselves along the stratum and evolution that they find themselves by way of. A grandmother and her lover drag themselves across the desert scape—fingers entwined—unable to stand for fear of being slaughtered. They will themselves forward until for a moment, entwined, they rest together in a church.

In reading Ayiti I am reminded of the miraculous migratory flood of a certain genus of Monarch butterfly that cross unimaginable distance from Canada to Angangueo, Michoacan, Mexico. The distance they cover is seen by many theorists as an “impossible” progression yet they continue to fly it, regardless. This is volition that makes continuance is asymptotic evolving–is the “reaching for something that could never be reached” but against all odds, continues

–

to be reached.

–

–

j/j hastain is the author of several cross-genre books including long past the presence of common (Say it with Stones Press) and trans-genre book libertine monk (Scrambler Press). j/j has poetry, prose, reviews, articles, mini-essays and mixed genre work published in many places online and in print.